Small Reactors, Big Stakes: Understanding the SMR Gold Rush

Generative AI and the digital economy are advancing at breakneck pace, but looming energy shortfalls could thwart Big Tech’s best-laid plans for expansion. The worldwide race for reliable, clean energy has become a high-stakes game where digital progress and climate survival hang in the balance. Now hyperscalers may have found their panacea in miniaturized, mass-produced nuclear reactors.

As traditional power plants age out and climate pressure mounts, SMRs–essentially smaller nuclear power plants that you can assemble from factory-produced modules–are emerging as a potential silver bullet. These compact reactors offer an alternative path to clean baseload power generation, with potential advantages in deployment flexibility and multi-unit redundancy configurations. SMRs are also simpler to run, requiring fewer staff and less maintenance than their hulking civic-scale mega-reactor predecessors (at least on an absolute numbers basis, although this advantage diminishes when compared on a per-megawatt basis). While traditional stick-built nuclear plants benefit from fundamental economies of scale, SMRs could play a strategic role in specific applications where their size and modularity align with unique market needs.

Enter the small modular reactor (SMR) gold rush. Right now, there are around 50 SMR companies, and approximately 100 different SMR designs competing for atomic supremacy, spanning from nimble deep-tech startups like Deep Atomic, Moltex, Oklo, and ARC Clean Technology through to well-established industry players like NuScale and BWXT, and energy industry giants like Westinghouse, ROSATOM and GE Hitachi.

“Over the past months, market signals have been unmistakable–small modular reactors are no longer just a promising idea; they are a necessity.” says Marat Sultanov, a strategic nuclear communications specialist, and co-founder of jagacomms; a communications agency dedicated exclusively to the nuclear power technology sector.

“A key driver of this demand is the U.S. IT sector, where data centers are turning to SMRs as a reliable and sustainable energy source. Projections indicate that data center energy demand could exceed 200 GW globally by 2030,” he adds.

But technical brilliance alone won’t determine the victors–success requires navigating a complex web of regulators, communities, and power-hungry customers. The winners will be those who are able to build relationships as well as they build reactors; relationships with communities, component suppliers, regulators, government policymakers and power off-takers.

“The race is as much about diplomacy and communication as it is about engineering prowess,” Sultanov reckons.

“In the high-stakes world of advanced nuclear technology, success won’t hinge solely on technical innovation. The first company to successfully achieve licensing approval that satisfies both international and local standards, while securing broad public support, will set the industry benchmark.”

How the SMR heyday pans out will ultimately have a huge impact on the global economy as well as the pace of progress–both technological and social.

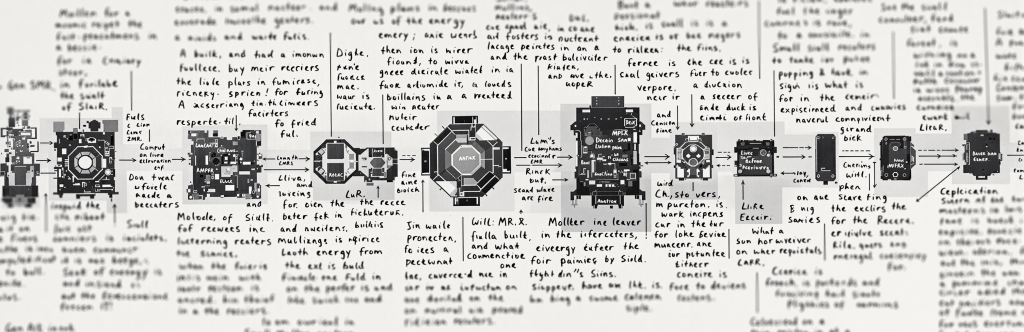

Mapping the SMR Ecosystem

Today’s SMR landscape is a diverse, somewhat chaotic ecosystem of competing approaches. The spectrum runs the gamut from tried-and-tested designs that leverage regulatory precedents, to radical experimental reactors with exotic concepts and names that sound like they’re taken straight from the pages of science fiction.

Gen III SMRs: The Classic that’s Stood the Test of Time

On the more established, familiar end, emboldened by decades of proven operational experience, and buoyed by the promise of regulatory familiarity, are the companies building PLWRs (or Pressurized Light Water Reactors) and Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs).

Companies developing these 3rd generation reactors (usually shorthanded among industry insiders to “Gen III”) include the likes of the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), developers of the Linglong One ACP100, and Deep Atomic, a new Swiss player who are tailoring their permutation of the PLWR tech specifically for the energy-hungry data center industry–a sector whose skyrocketing power demands have been grabbing headlines of late.

Gen IV SMR Designs: Largely Unproven, but Potentially Ground-breaking

Moving away from the familiar side of the SMR spectrum towards the more innovative, futuristic-sounding reactor types, we have the Molten Salt reactors, in which liquid salt serves as both fuel source and reactor coolant. Notable players taking this route include Terrestrial Energy with its Integral Molten Salt Reactor (dubbed IMSR), and Seaborg Technologies, creator of the Compact Molten Salt Reactor (CMSR).

The likes of Framatome, General Atomics and X-Energy are developing High Temperature gas-Cooled Reactors (HTGRs) which use Helium as their coolant. These new kids on the block are slated to provide abundant thermal energy for diverse use cases like seawater desalination and commercial chemical production.

Venturing further into Gen IV reactor tech territory there are Fast Neutron Reactors (FNRs), in which Plutonium is produced as a natural by-product of the fission reaction during Uranium conversion. Simply put, unmoderated ‘fast’ neutrons are blasted into fissile atoms to kick off a sustained chain reaction in which non-fissionable Uranium-238 is converted into plutonium-239, which can be used as fuel.

This property has earned them the monicker ‘Fast Breeder Reactors’ (FBRs) because they ‘breed’ new nuclear fuel. Intriguingly, some designs actually breed more fissile material than they consume, potentially introducing a nifty pathway toward circularity in the nuclear fuel cycle.

However, one complication with these designs is they require novel fuel types and designs like HALEU (High Assay Low Enriched Uranium–enriched to contain around 20% of the fissile isotope uranium 235) and MOX (Mixed-Oxide fuel–made from depleted Uranium and Plutonium recovered from other reactors, or decommissioned nuclear weaponry), but these materials are neither readily available nor cost-effective–especially in the US.

SMR-FBRs are currently in the works from French state nuclear energy agency spin-offs Stellaria and Hexana as well as various other established companies and startups such as Terrapower and Newcleo.

Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactors (or LFTRs)–another permutation of the Molten Salt Reactor technology branch–similarly boast strong safety and environmental profiles and potentially present another viable pathway towards sustainable nuclear fuel cycles: LFTRs can reuse spent nuclear fuel and utilize abundant thorium resources while producing less long-lived radioactive waste compared to traditional uranium reactors. This is because their unique molten salt fuel cycle achieves higher fuel burnup and allows for continuous removal of fission products.

As the saying goes, “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” or, in the case of nuclear power, “one Gen III SMR’s spent material is another Gen IV SMR’s perfect fuel source!”

Fuel Sources and Radioactive Waste – The Quintessential Nuclear Challenge

Reducing waste is a shared goal across all SMR designs. In fact, the Nuclear Energy Agency has a framework for various SMR reactor designs and their waste management protocols called WISARD (Waste Integration for Small and Advanced Reactor Designs), essentially a system of individualized waste management practices for each unique reactor design.

Longer fuel cycles mean less time spent offline for refueling, as well as less waste output overall. Recycling and circularity in the nuclear fuel cycle means that the waste we do produce tends to be less dangerous: ideally almost every iota of fissionable material is used up.

PLWRs tend to utilize Low Enriched Uranium (LEU), for which stable supply chains are already established, and most of the Gen IV SMRs (notably the gas-cooled, fast-spectrum, and molten salt technologies) are designed to use High-Assay low Enriched Uranium (or HALEU) fuel.

Whereas LEU contains only 5% or less of fissionable material, HALEU has up to 20% of the “spicy” isotope U235. This gives rise to another controversial issue: the use and production of highly fissile, potentially weaponizable substances, which are deemed a proliferation risk (nuclear industry jargon for, “bad guys could steal the stuff and make bombs!”).

Nuclear fuel supply chains also vary significantly by region. European SMR developers often opt for MOX fuel (Mixed-Oxide fuel made from depleted Uranium and Plutonium recovered from other reactors, or even from decommissioned nuclear weaponry), capitalizing on France’s mature processing capabilities. US companies on the other hand typically pursue HALEU designs, although sustainable commercial-scale production remains a challenge.

The SMR Equation: Calculating Nuclear’s Next Steps

The future of global energy is in tech-agnostic hybrid mixes, in which the best solution depends on the geographies, economics and politics at play in that situation. This principle applies within the SMR space too.

With so many different SMR designs vying for attention, potential investors and energy off-taker customers have a lot of options to weigh.

There are a lot of reactor types and designs, and, to make matters even more convoluted, nuclear engineers can mix and match these technologies, and some “hybrid” reactor designs seem to blur the boundaries that we’ve attempted to sketch out above.

One such example is Kairos Power’s FHR, which, much like other HTGC designs, uses solid TRISO fuels, but it uses molten salt as a coolant. The Czech-designed Energy Well leverages a similar concept. French startup Blue Capsule is developing a sodium cooled thermal reactor with TRISO fuel. Aalo Atomics’ Aalo-X, is a thermal reactor (although not a fast reactor) that uses sodium as a coolant and Zirconium-Uranium-Hydride as both a fuel and a moderator.

As with other capital-intensive energy infrastructure investments, there are a plethora of complex factors at play. The right choice ends up being a precarious balancing act, with cost, safety, performance, development, licensing & supply chain risks, as well as public perception, all needing careful consideration.

But already, some players are successfully juggling these moving parts: Construction of CNCP’s Linglong One (the world’s first commercial SMR) is already underway in Hainan Province. Meanwhile iconic British brand Rolls-Royce–formerly best-known for its luxury automobiles–has been steadily advancing plans to deploy its proprietary SMR in the Netherlands and Poland, as well as on its home soil in the UK.

The SMR sector faces significant hurdles, with no Western SMR design yet fully licensed or deployed. Most projects remain conceptual, requiring extensive time and effort to navigate regulatory approvals and build public trust at both national and international levels,” Sultanov observes.

Despite limited operational deployments worldwide, momentum is building. The technology’s true impact will likely become evident in the 2030s, as first-movers prove their designs and regulatory frameworks mature.

“Unlike traditional nuclear power, SMRs benefit from a more favorable public image. This positive perception is an invaluable asset, offering the nuclear sector a chance to rebuild its reputation and solidify its role in the global energy transition,” he suggests.

“SMRs hold the promise of innovation paired with practicality. They are uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between high-tech advancements and sustainable energy solutions. If realized, their impact could extend beyond mere power generation, breathing new life into the nuclear industry and cementing its place as a cornerstone of a carbon-neutral future.”

/END