Text, Typography, and Trouble: Inside the AI Art Engine That Sparked a Cultural War

- Published 31 March 20205

- Updated 02 April 2025

Last week saw yet another major cultural moment in AI, and a historic inflection point at the intersection of art and technology. More importantly, that tingling feeling of awe, and sense of exposure to a powerful, magical force has returned to AI for the first time in a long while. With no more than the usual amount of fanfare, OpenAI dropped a new version of ChatGPT that happens to be the most potent AI art generator we’ve seen yet.

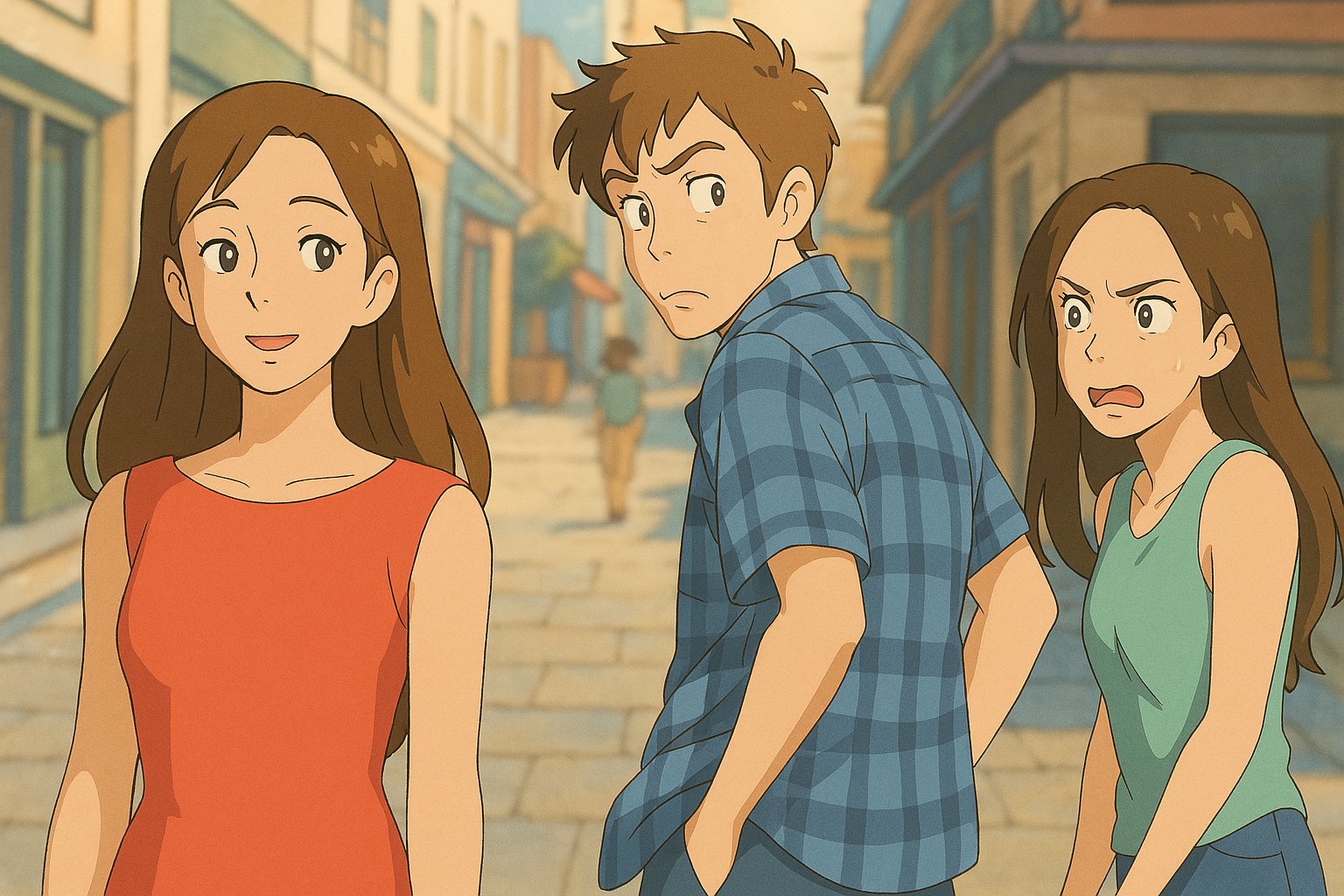

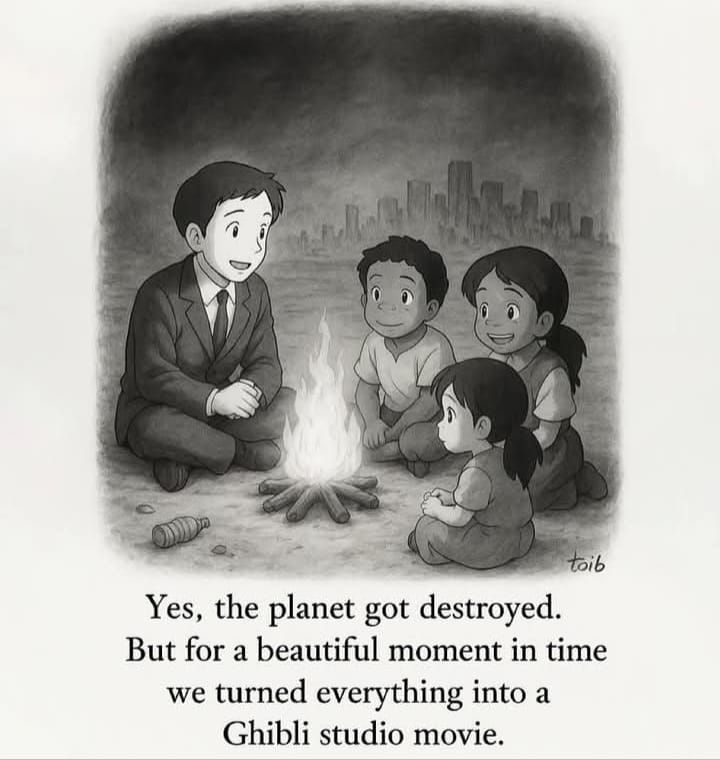

This led to a strange viral moment that ‘broke the internet’ – The world began using the newfound unchecked power of deep style transfer at their fingertips to envision anything and everything in what is perhaps the most charming aesthetic known to humankind – Studio Ghibli style.

The situation reached a veritable boiling point when Altman declared, only half jokingly, that users’ enthusiastic use of the new image engine was melting GPUs in their data centers.

The torrent of Ghiblified images speaks to just how intuitive and accessible this new model is – and hints at the scale of the disruption to come. Previously only AI art geeks and power users – with their self-trained LoRAs and convoluted ComfyUI workflows – were able to convincingly Ghiblify at whim – although tools like Leonardo AI do already boast decent style reference capabilities, and have for some time now.

But I suspect that the ongoing Ghiblification debacle is actually an outward symptom of a collective, social immune system response flare-up; a response to what is ultimately a hugely disruptive, game-changing (and threatening) tech innovation.

The relentless pace of AI progress engenders a subconscious anxiety about the growing time lag between our computers’ accelerating capabilities and the market economy’s adaptations. Is this moment a manifestation of these anxieties; a kind of internet SOS smoke signal disguised as humour?

“From the first cave paintings to modern infographics, humans have used visual imagery to communicate, persuade, and analyze—not just to decorate… …From logos to diagrams, images can convey precise meaning when augmented with symbols that refer to shared language and experience.”

https://openai.com/index/introducing-4o-image-generation/

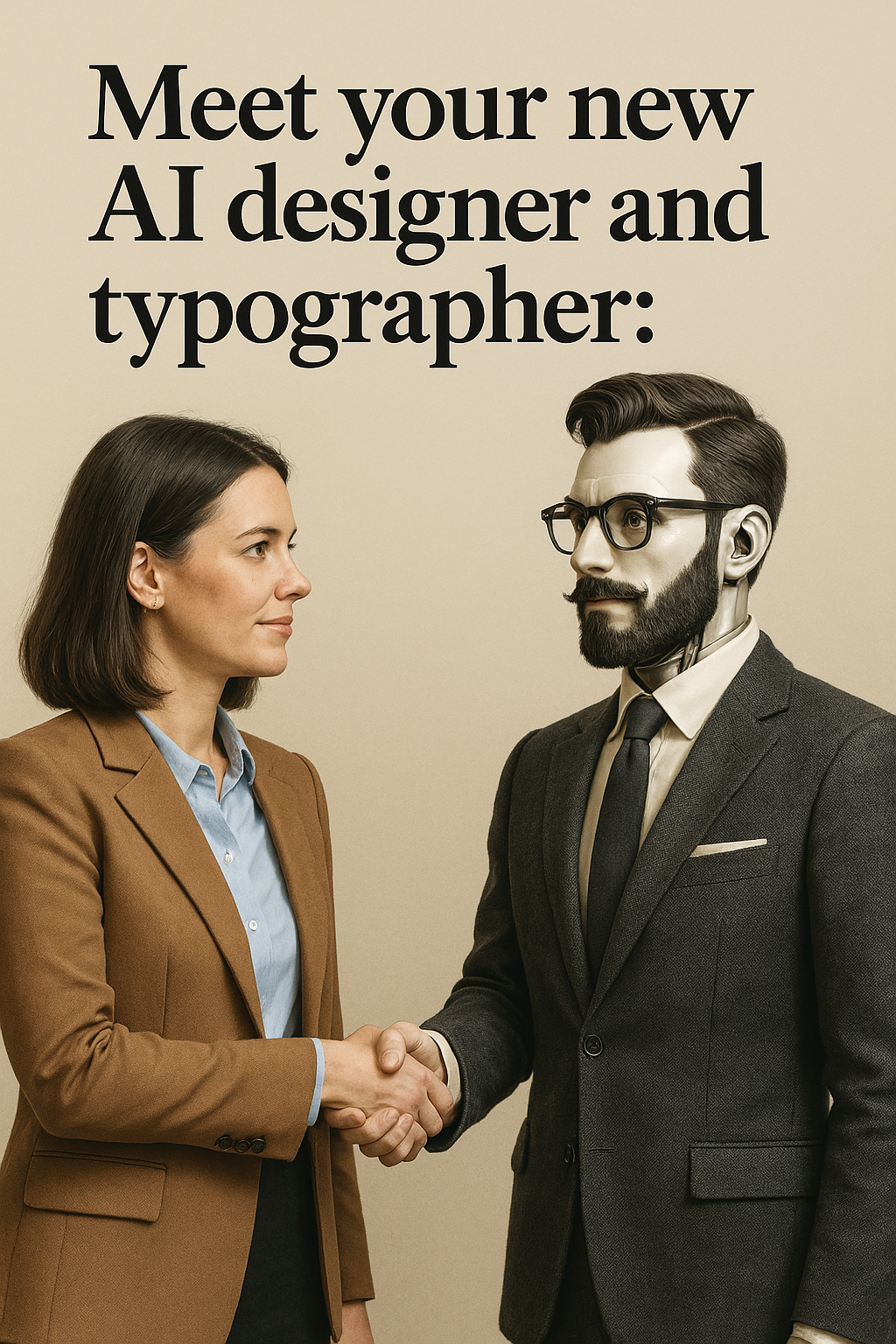

The capability improvements in 4o are a genuine transformation in machine-generated visual communication. For the first time, an AI can seamlessly blend typography with imagery while maintaining both aesthetic cohesion and semantic meaning. Under the hood the model has seemingly effectively breached the ‘cognitive’ chasm between seeing and reading – which, in our own human brains, happen as distinct processes with their own separate neural correlates and thought patterns.

While the internet giggles at Ghiblifications of popular memes, the truly revolutionary aspects of this technology remain underexplored. After testing out the new system (which is available in ChatGPT itself as well as the Sora page, albeit currently only for paid plans at time of writing), I genuinely believe humanity has now crossed a significant technological threshold that everyone in creative industries needs to watch.

Below I’ll dive a little deeper into the new 4o’s unprecedented accuracy in text rendering, the intuitive conversation-based creation process, and the implications for our entire ecosystem of corporate creatives, artists, and designers, before taking it for a test drive.

AI Art Engines are a Major Industry

The image generation space is a very crowded vibrant marketplace, with many strong players competing for our bucks. Previously, Ideogram, Recraft, MidJourney, and Flux 1.1 Pro Ultra were all legitimate contenders for top dog among AI art engines, all boasting fairly accurate in-image typography, complex-prompt following, and reasonable overall image coherence. Ideogram dropped version 3, which is phenomenal, but was nonetheless completely overshadowed by the new 4o.

Recently Google made a splash with Gemini 2.0 Flash, which saw it briefly make a run for the podium, but verdicts from around the web are in: OpenAI cooked with this new model, and it has now taken the top spot in the zeitgeist by a long shot. At this point it basically is the visual cortex of our hivemind.

There’s an interesting feedback cycle of engineering and reverse engineering that bounces between closed- and open-source paradigms in the world of AI art engines.

This is an oversimplification, but typically, a proprietary model is released, which is then reverse engineered by the open-source community, who sometimes even manage to improve (if subjectively) the average quality of outputs in the process. The innovative shoestring-budget architecture of the open source pioneers is then in turn replicated and scaled by big tech.

This is because it’s often the power users of open source models who are passionate enough to squeeze as much as they can out of limited compute resources, and, in so doing, manage to bootstrap solutions in the relentless pursuit of image quality.

Classic examples are the advent of fine-tuning techniques and LoRAs for mastering specific aesthetics, and the inclusion of pose-adherent models (like ControlNet) into stable diffusion-based workflows, as well as optimization via complex multi-step architectures, in which models and processes are chained and combined in node-based free-form tools like ComfyUI.

All of this was largely driven by the open source community, likely inspiring the closed source, big tech guys to up their game, and to replicate certain key methods and techniques.

Also, at times the closed-source models get lobotomised, because of copyright infringements or other legal concerns, and closed source guys, rebellious by nature, typically then work to re-establish the nerfed capabilities in their models.

That said, this model does things in a fundamentally different way under the hood to arrive at these astonishingly hi-fidelity results.

What Sets 4o Apart Under the Hood – Multimodality and Regression

According to the creators, they achieved this technological marvel by integrating textual and visual reasoning into a single stream of machine ‘thought’. Impressive!

The new 4o’s architecture is fundamentally different to other image generators. Unlike previous systems that essentially bolted different capabilities together (a bit like wiring a camera up to a typewriter), 4o was built from the ground up to understand both text and images as part of the same conversation.

The system doesn’t switch between different modes of thinking; visual and textual understanding flow through the same neural pathways. This seamless integration explains why typography works so well in 4o’s images.

Most popular image generators like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and earlier DALL-E versions use diffusion models – they start with random visual noise and then iteratively carve away the noise until a coherent image emerges. It’s somewhat like sculpting in that it begins with a formless block which gets gradually chipped away until you reveal the statue hidden within.

In contrast, regressive models – which appears to be what 4o employs under the hood – work more like human imagination. Rather than starting with noise, they build the image element by element, predicting what comes next based on context, just like how vanilla LLMS “predict the next token” to produce a coherent sentence. This approach enables much tighter integration between conceptual understanding and visual representation, particularly when it comes to text within images.

For creators, this means we can work with the AI in a more natural way. We could do so before, but results would be questionable, and you’d lose all semblance of fine-grained creative control, making the process of creation a bit like gambling, but with dopamine receptors instead of poker chips.

With 4o, the creative process feels fun and fluid, some mixed feelings at having relinquished more creative control than usual notwithstanding. You can start with a vague concept, or even a napkin sketch, see what the model comes up with, and then refine with specific feedback, and watch in wonder as your silliest thoughts are dispatched with mechanistic efficiency.

“Make the champagne look more opulent and expensive”; “Convert my friend into a spaghetti monster with a traditional Celtic helm doing parkour” or “Give this photo the rich deep colour scheme of a fine flask of cognac sitting atop a smoky bar” are all legitimate instructions, and no hassle for 4o.

The Ghibli Controversy: Copyright, Ethics & Creativity

As we’ve seen, the new 4o image model has been devastatingly effective, even prompting the Ghiblification spree and ensuing brouhaha. Over the past few days, may have seen some of these Ghiblified images, or even mini-movies – reimaginings of iconic film snippets – floating around your feeds.

OpenAI’s marketing team are subtle and crafty. I’d wager this was part of their promotional strategy all along. Altman himself changed his profile picture to a Ghiblified Sam in alignment, further encouraging the viral trend.

Some commentators have speculated that Ghibli was strategically targeted as Japan’s copyright law uniquely favours innovation in AI over artists’ rights, in that it allows scraping, deeming the process – as I and many other tend to do – more akin to learning and inspiration, as opposed to theft or misappropriation.

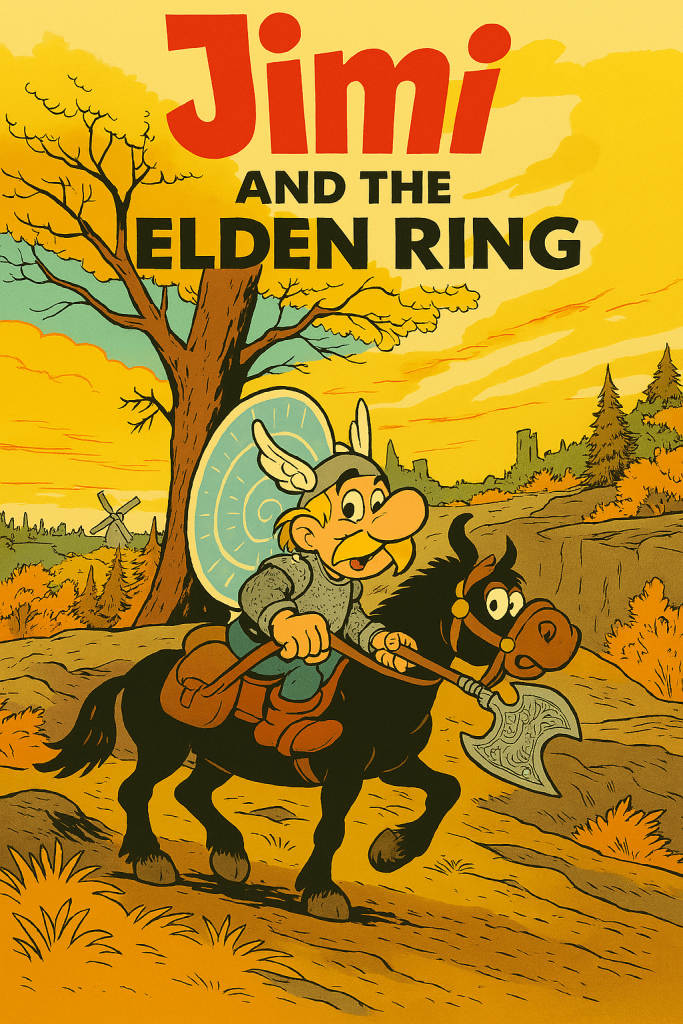

At the time I made this joke film poster, I had no idea that the Ghiblification trend would blow up the very next day!

But the Ghibli controversy is merely the latest skirmish in an increasingly tense culture war between AI-augmented creators and traditional artists. In the past years, the most zealously AI-opposed among traditional artists have even gone so far in their attempts to resist this technology as to start dataset poisoning campaigns – deliberately uploading watermarked or manipulated versions of their work designed to confuse AI training crawl-scrapers.

These specially designed adversarial images harbour patterns invisible to humans, but that, once injected, ostensibly corrupt model training. Online communities have even developed tools to quickly and imperceptibly ‘poison’ pictures, for artists to run their images through, before sharing them with the world online.

Yet 4o’s remarkable overnight success suggests these tactics have been largely ineffective. On the other hand, GPT-4o boasts C2PA metadata embedding, essentially making the provenance of all its outputs easily detectable as AI as opposed to “real” images.

The Ghiblification saga also begs the difficult question of what ‘style’ actually is. We instinctively know that style exists, but, much like ‘consciousness’, ‘beauty’, and ‘artistic soul’, we are nowhere near agreeing on a firm consensus definition for it – be it in music, writing or visual art. At this point, AI may understand what ‘style’ truly is more perfectly than we do ourselves, if only through brute force and pattern recognition. Also, since the legal word relies on firm, concrete definitions, style itself isn’t normally something that can be protected by copyright law.

Immersed in their flow-states, skilled creatives, artists and musicians will make a thousand tiny decisions per minute – many of them unconsciously – that amalgamate to arrive at a signature style.

One of my friends – an accomplished illustrator – once said to me that ‘style is the combination of all your mistakes.” That idea – that style results from tiny flaws in each of those micro-decisions, and that a true radiant beauty shines through from our very inability to achieve the artistic perfection we’re perpetually grasping for – that really stuck with me.

Unpopular opinion: A style like Ghibli’s, one that brings so much joy to so many is, much like the seatbelt that Volvo famously eschewed intellectual proprietorship for, should maybe even be a public good, and belong to the collective. This is not to say that the artists should not be compensated for their profound contributions to global art. They most certainly should.

But the story speaks to deeper questions about ownership in the age of machine learning. When an AI model trains on millions of images, including those created by living artists, shouldn’t the resulting capabilities likewise be considered a public good that belongs to everyone?

These models are built upon the collective cultural output of humanity over generations. Multimodal models’ like 4o and its successors are being trained on datasets that likely include everything you and I have ever put onto the web over our entire lives.

For AI to become socially sanctioned, and overcome its currently tarnished branding, we need to somehow make everyone the direct economic beneficiaries of their own cultural contributions over a lifetime – or at least push harder towards truly democratized access to these tools.

“I am utterly disgusted… …I strongly feel this is an insult to life itself.”

An earlier remark by Hayao Miyazaki on generative AI, that has resurfaced of late in light of the controversy.

I am of course an ardent Ghibli fan. Their creations have been nothing short of formative for me. Considering the immense time, effort and attention to detail these artists pour into their work, I’d have to concede that we are losing something special as this new magic brush takes hold. But, at the same time, as with all powerful technologies, we are gaining something important as well – namely the power to close the gap between what we see in our minds’ eye, and fully-realised digital imagery, in the time it would take to sketch a doodle.

Although probably of little consolation to Miyazaki; the furore arguably promotes Studio Ghibli. Far from diminishing their brand, this memetic moment has introduced their distinctive, iconic aesthetic to new audiences and reinforced their cultural significance, which is well-deserved, and only fair, methinks. The slew of Ghibli-inspired creations is a testament to the studio’s profound influence on visual storytelling, and how deeply their artistic vision resonates across generations.

Where the Tech is Headed

It’s worth pausing here to consider the broader context of AI disruption, of which I think we’ll see a lot more of in 2025, to put it mildly. The case of the EdTech service Chegg – which has plummeted from market leader to struggling survivor – speaks volumes. While post-pandemic trends played a role, the reason, in a nutshell, is that systems like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude now do for free (or at minimal cost) what students previously paid Chegg’s human tutors to do.

Needless to say, us creative professionals have reason to feel uneasy about just how quickly the tech is improving nowadays. “Agentic” became a word last year. This year, if your job involves being clever on a computer, agentic systems that transform your workstation into a self-steering workhorse are coming for you. We’ll likely have to either beat ’em or join ’em.

Now, it feels like even the soul of the artist is under fire, and I think we need to admit to ourselves that this new model appears – more than previous iterations of the tech- to genuinely display the qualities that we humans call “creativity”.

Humans inherently exist within chaotic, organic systems, whereas machines operate within the bounded rules of binary computation. To me that fundamental difference suggests that AI’s approach to human-level capabilities will always be asymptotic, and that human ingenuity will invariably find an edge, even as the cost of creation (and creatives) is driven down towards zero. If not through direct competition, then through adaptation, mastery over the new paradigms, and human-machine collaboration.

As an aside, there’s an important distinction in how we should think about Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). The common definition; “a system that can automate the majority of economically valuable work”, misses something crucial. True intelligence lies in the ability to efficiently acquire new skills outside of training data.

The nature of monetizable creativity is shifting. There is cause for concern, but also, I believe, for cautious optimism. On balance it’s an exciting time to be a creator!

Experiments:

Stick around as I take 4o through its paces and see if I can learn some tricks about how to get the most out of it below:

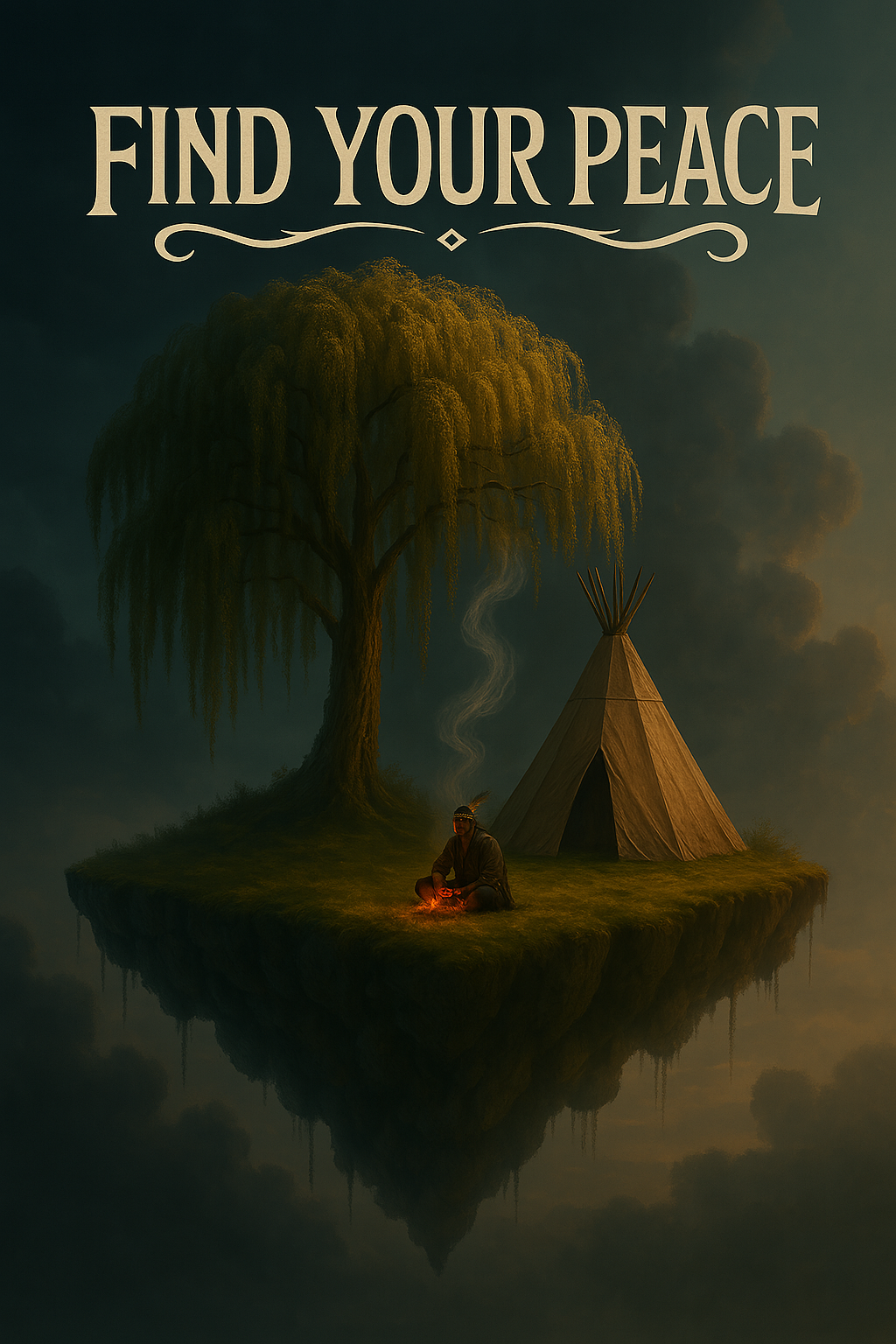

Should creatives and graphic designers be worried? 🤔

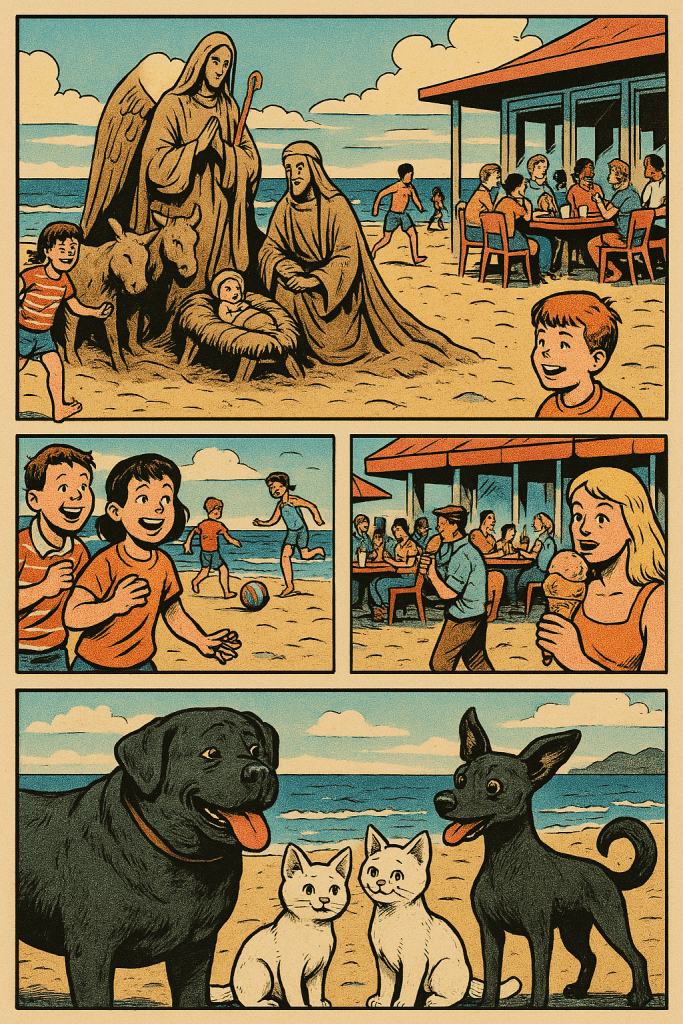

For a start, here’s a short comic-style story I prompted for my son, who enjoys the video game Elden Ring, as well as the Asterix & Obelix series of books. I found the references to both texts to be spot-on in the below:

I uploaded an in-game screenshot depicting one of the more impressive vistas in From Software’s exquisite video game, and got started with simple prompts like:

“Please do an Asterix and Obelix style rendition of this image in the iconic old-skool comic book style of those stories.” And, “Fantastic! Could you replace the Asterix with “Jimi”?”

In that experiment, I kind of let the AI take over and do its thing. This approach has a a lot in common with Vibe Coding, where you essentially let the AI model take the reins.

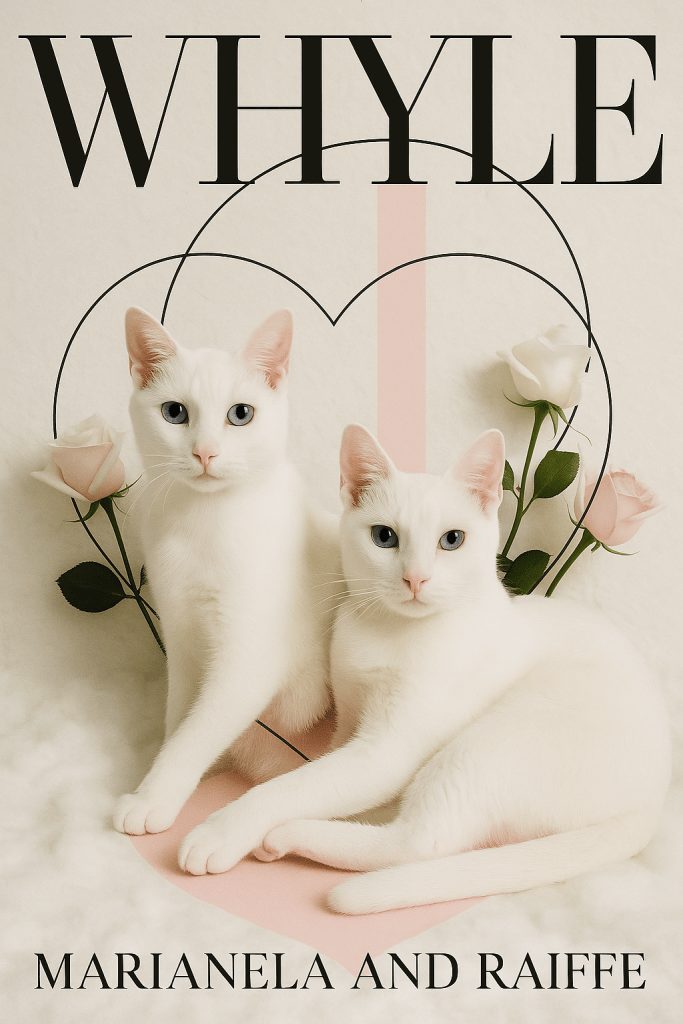

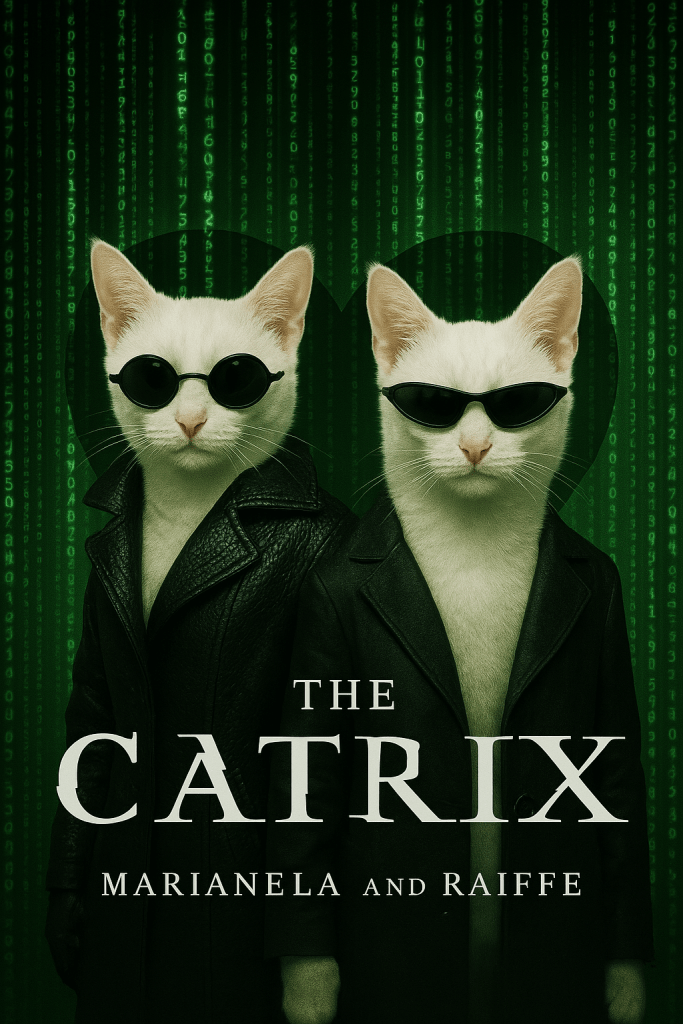

Next, I decided to really take the model for a spin and see what it could do, using this adorable photo of our family kittens Marianela and Raiffe, who one day were serendipitously captured laying in heart formation. ♡

I ended up having way too much fun with this one! Here I think 4o really shone. Note how it even managed to adhere to my somewhat unhinged requests about duly crediting other family pets for their roles in these celebrated cinematic greats.

What’s cool about this system: because the image prompting is integrated into the chat interface, once the model gets what you’re up to, you can near-effortlessly direct proceedings through a kind of nonchalant banter, with simple inputs like, “Next, do The CATIATOR starring … you guessed it!”

Sometimes you have to follow up with requests to fix mistakes, or nudge it in the right direction with clear firm instruction, like: “Add gorgeous intricate cursive calligraphy: “Marianela and Raiffe”

Next, it’s time to really put it through its paces with a hard challenge that would have been inconceivable for previous versions of this tech.

Prompt: “Please draw a poem in the shape of Africa. Use the lyrics from the song Africa by Toto…”

A noble attempt, but not great. Here we start to bump up against the limits of our wunderkind’s capabilities. So that one was perhaps a fail. “Af- ooh-hoo” indeed!

Next, the Apple-Frica mock ad and ensuing pandemonium:

Prompt: “Please make me a magazine ad for Apple-Frica Apple company. The Juiciest apples on the continent. The add features a stylish photograph of a large apple shaped exactly like the continent of Africa”

Follow-up prompts: “Now do an action sequence Hollywood still wherein an aardvark is entrusted to transport the Africa-shaped delicious red apple across a river, but is pursued by a hungry crocodile!” & “Add a funny tag line, something about AppleFrica, Aardvarks and Crocs perhaps?”

Very cool!

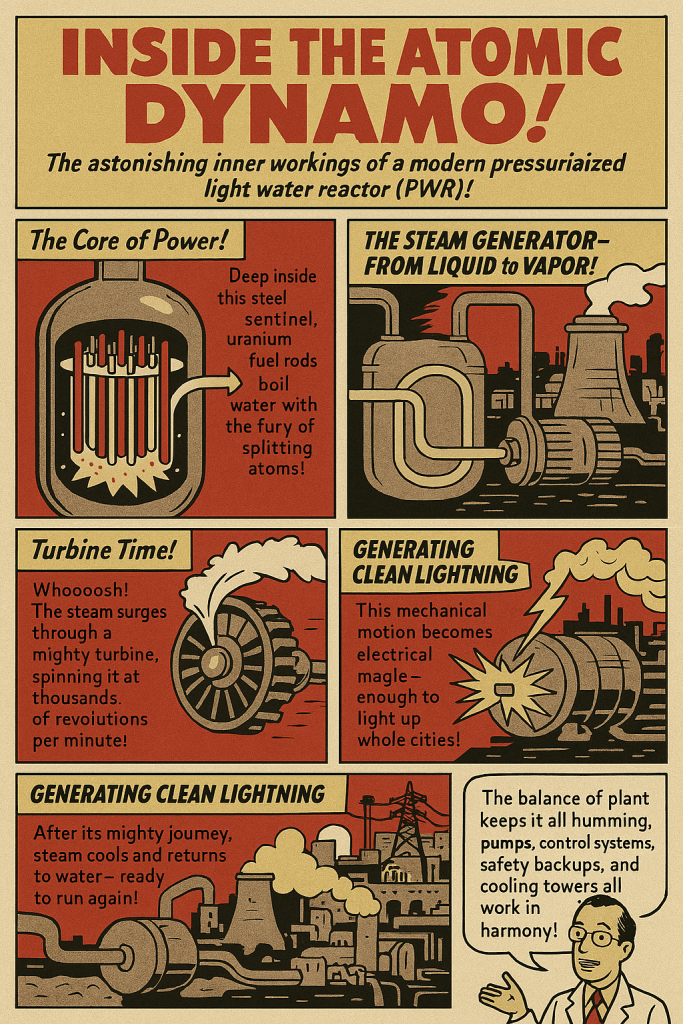

As another difficult test, I asked for, “An accurate 40’s retro comic book style infographic about the inner workings of a modern pressurized light water nuclear fission reactor and balance of plant design.”

This is notably better than what other models could do with the same prompt, but again we start to run into various incoherencies.

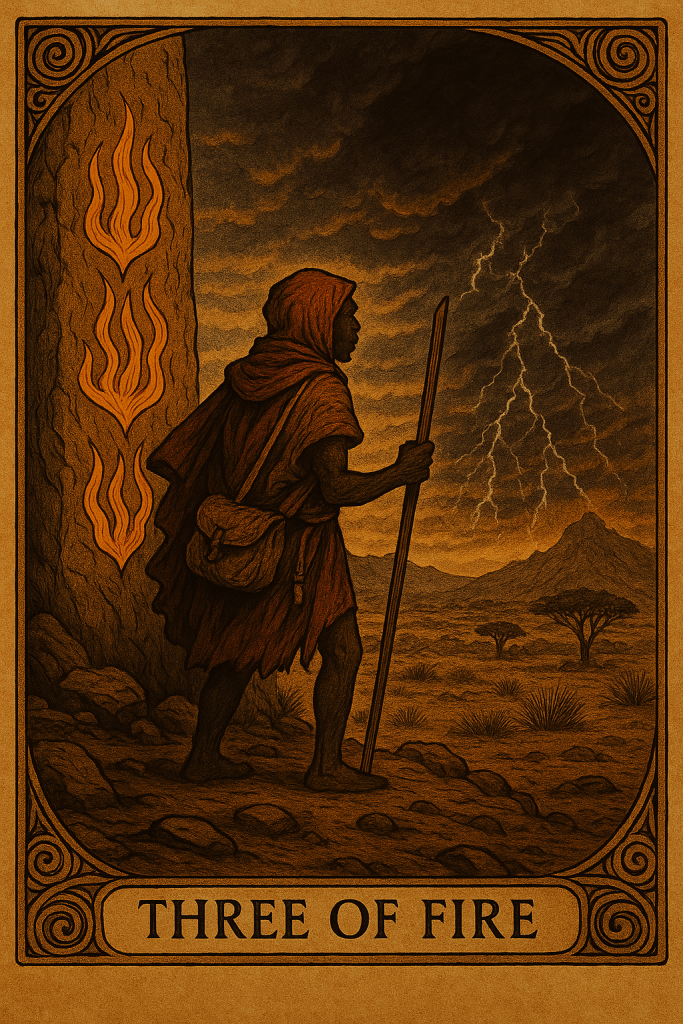

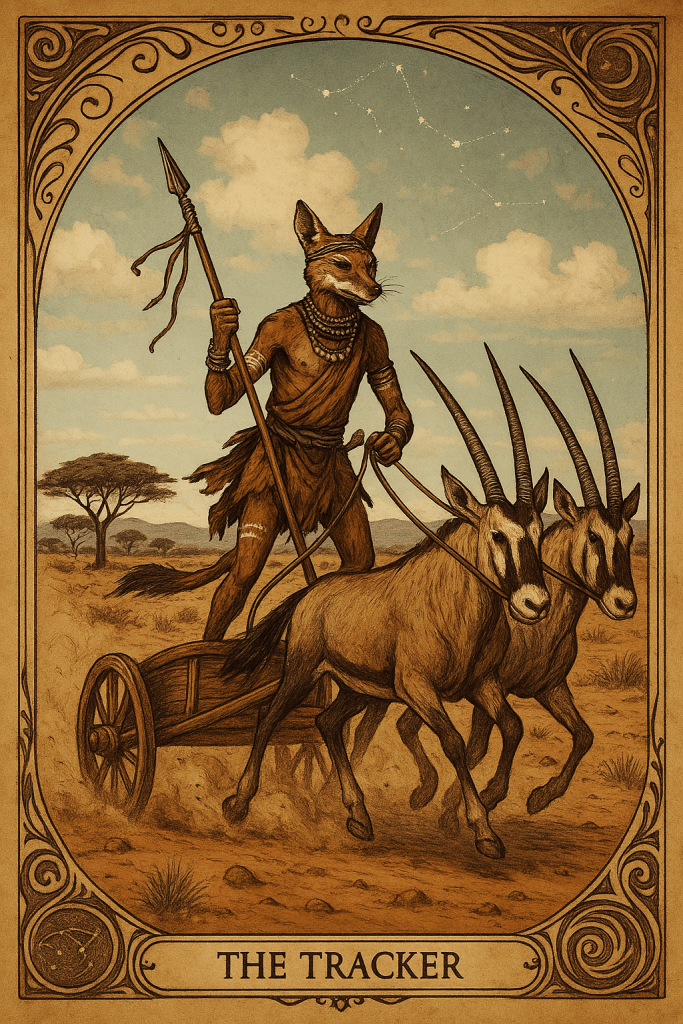

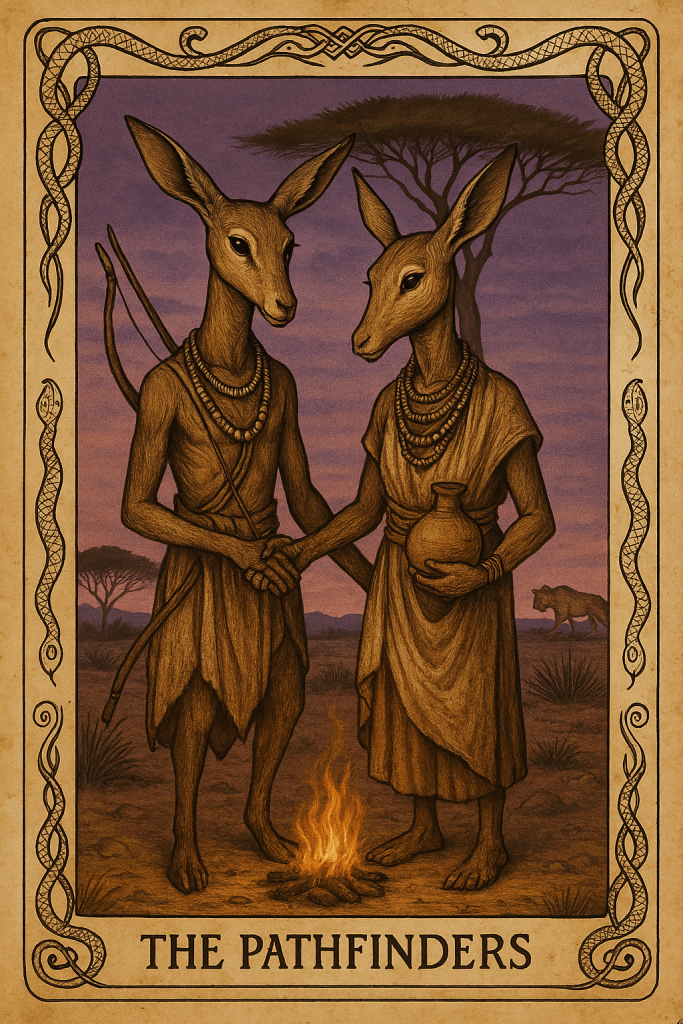

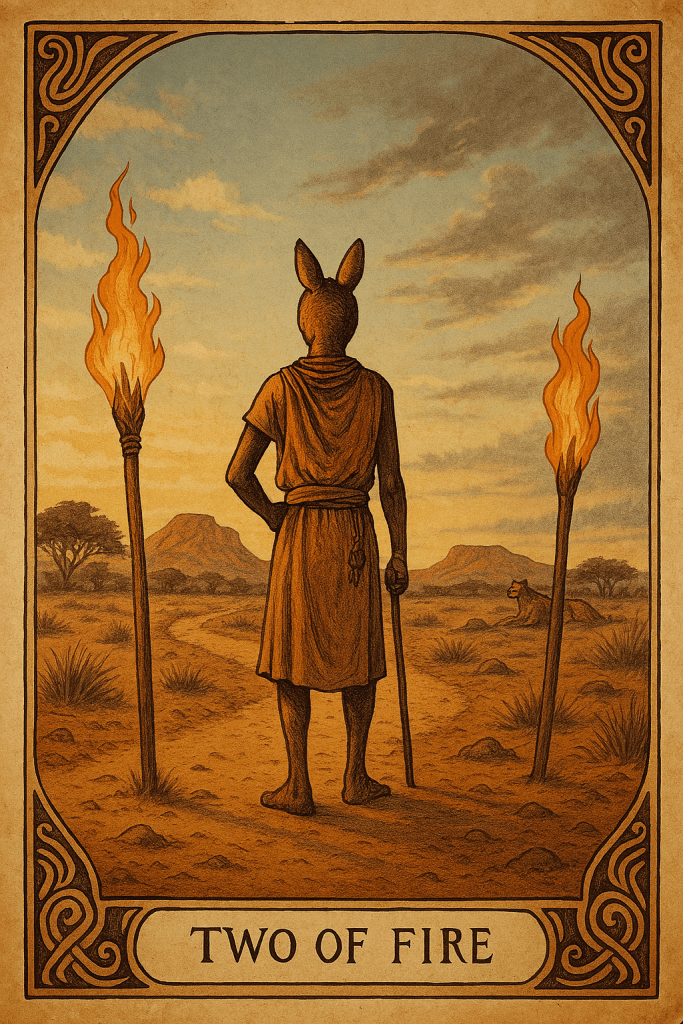

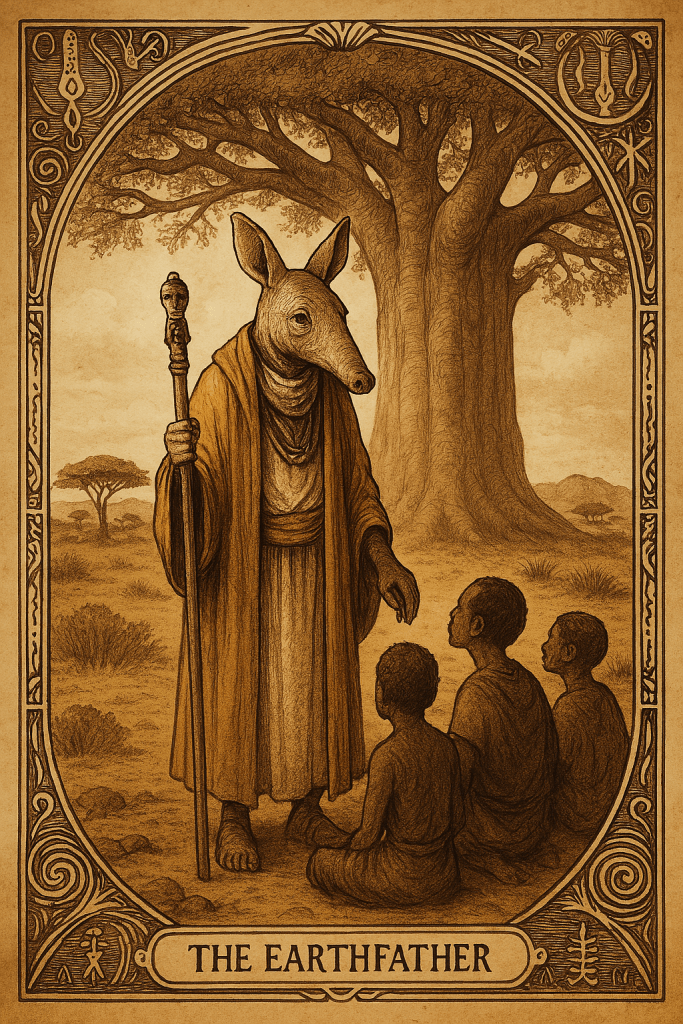

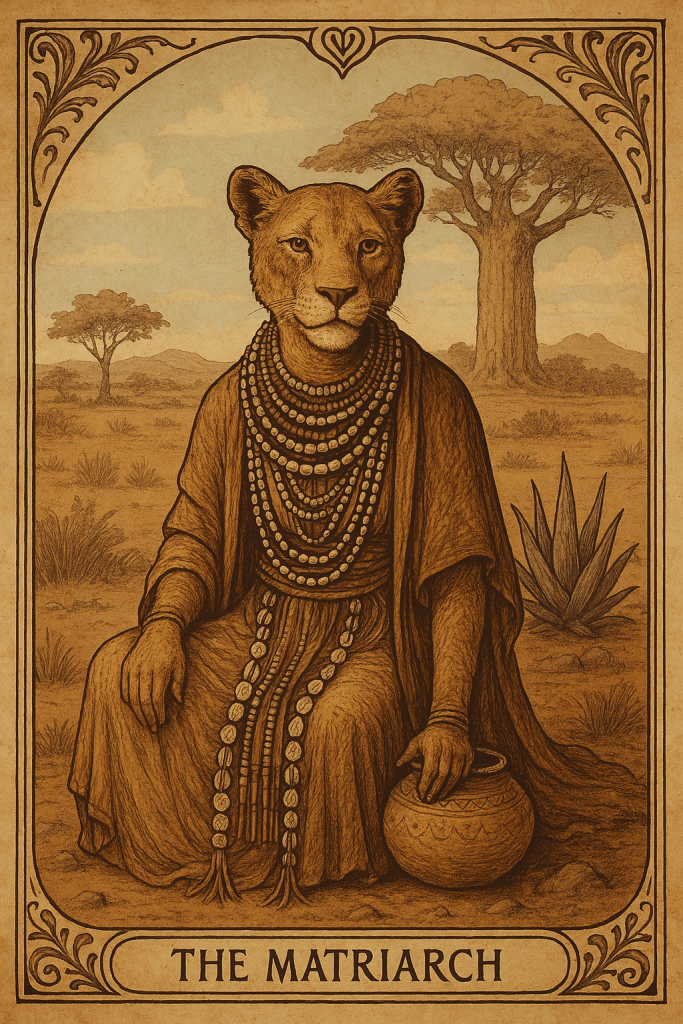

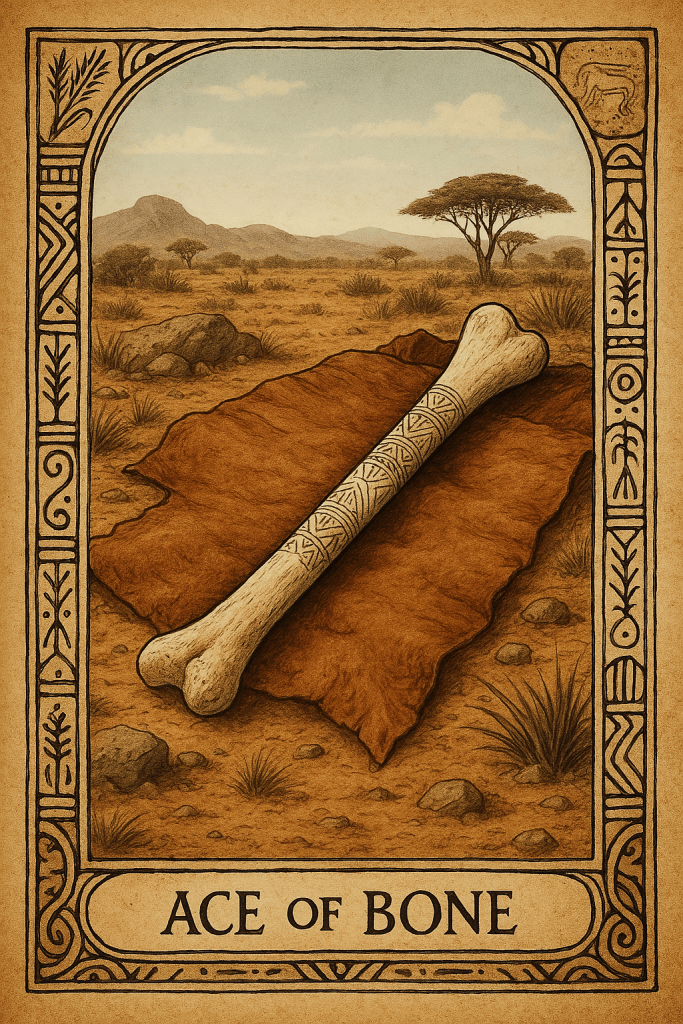

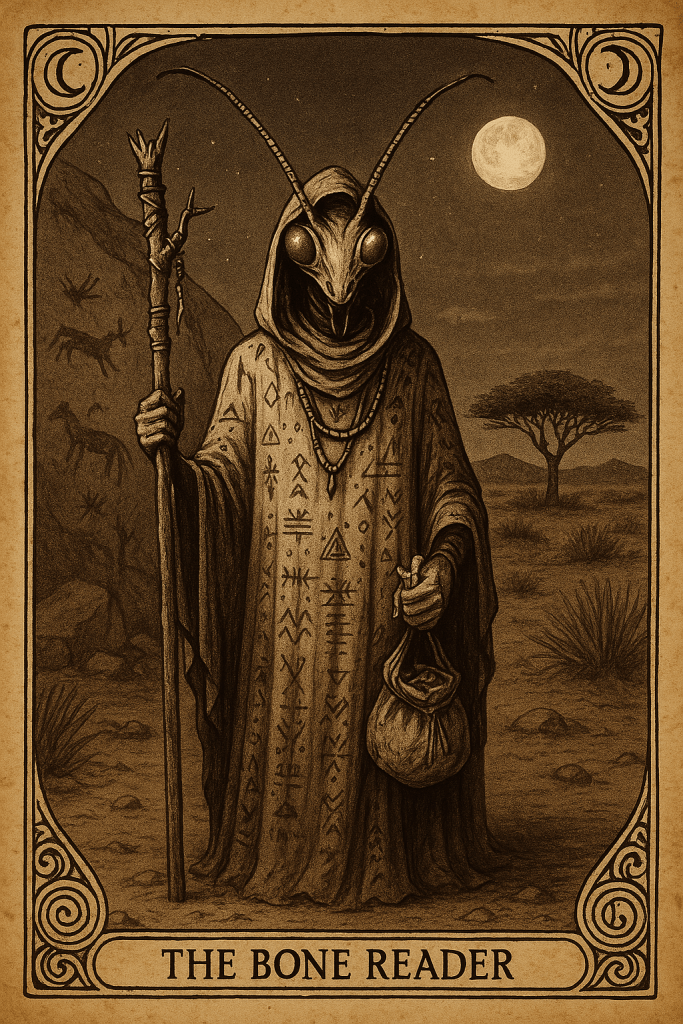

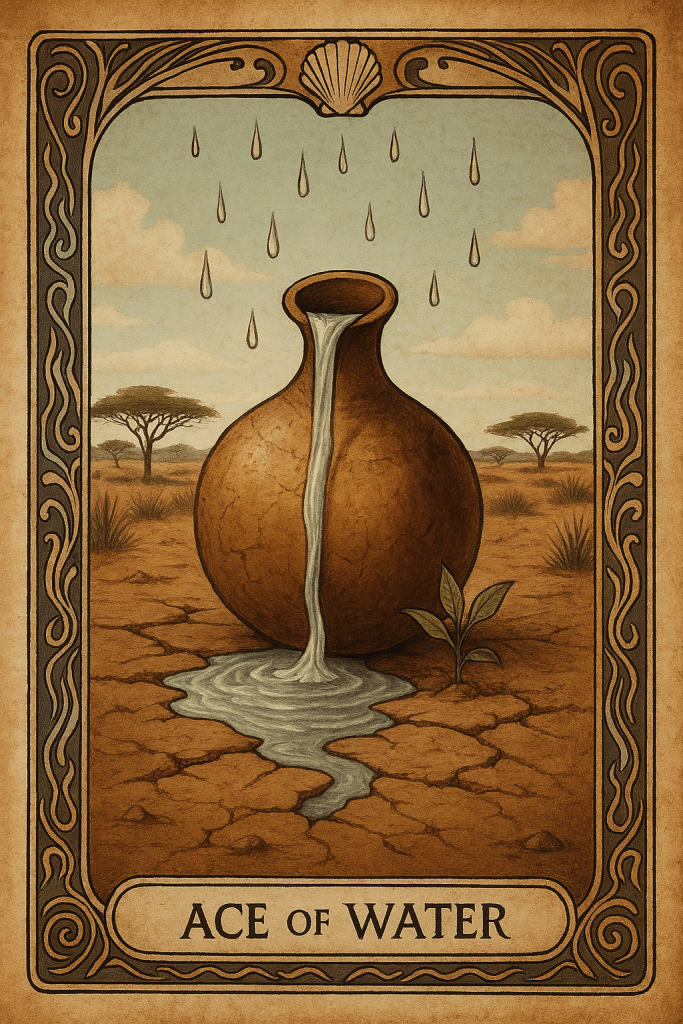

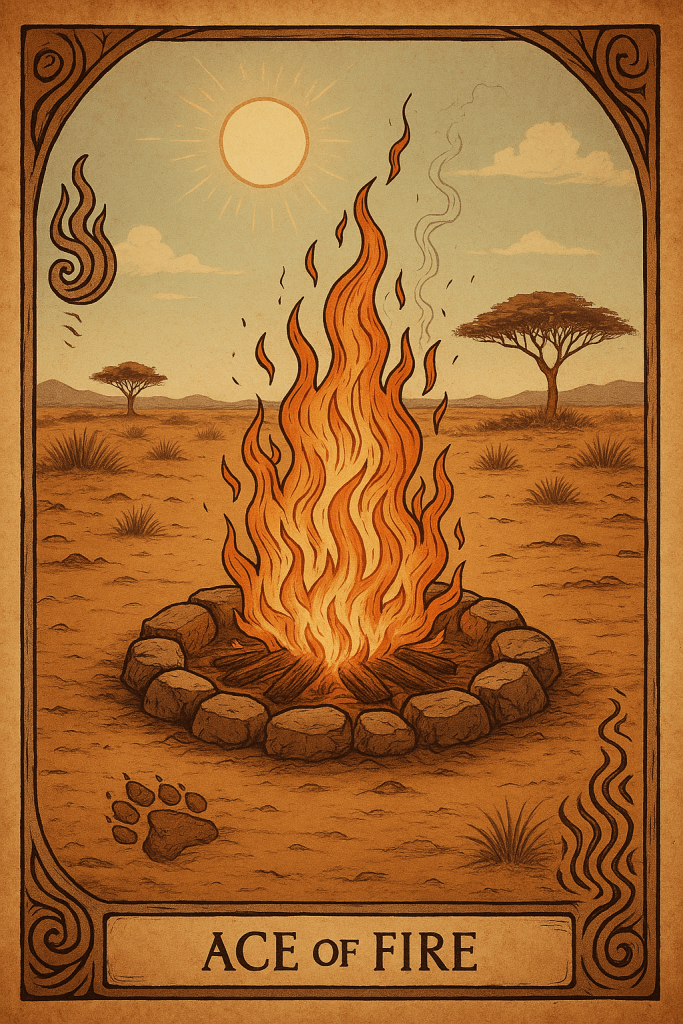

I’d always wanted to see a tarot deck inspired by Southern Africa mythology and lore. I simply fed in a single image as a style reference, and then let it go ahead and create to its heart’s content. Here the model excels, perhaps because the typography is relatively minimal. I must say, these ones were exquisite, and really feel like they have soul and a style all of their own. I hope I manage to get these printed as an actual physical deck someday!

You can design your own workflows and loops of quick ideation and iteration. Whether you edit the image by simply responding inline in the chat, or as a direct response to the image doesn’t seem to make any difference.

The closer adherence to the composition of input images is a game-changer!

On the Sora image gallery you can see the kinds of irreverent unhinged eye candy that the world’s creatives are churning out. It’s pretty wild!

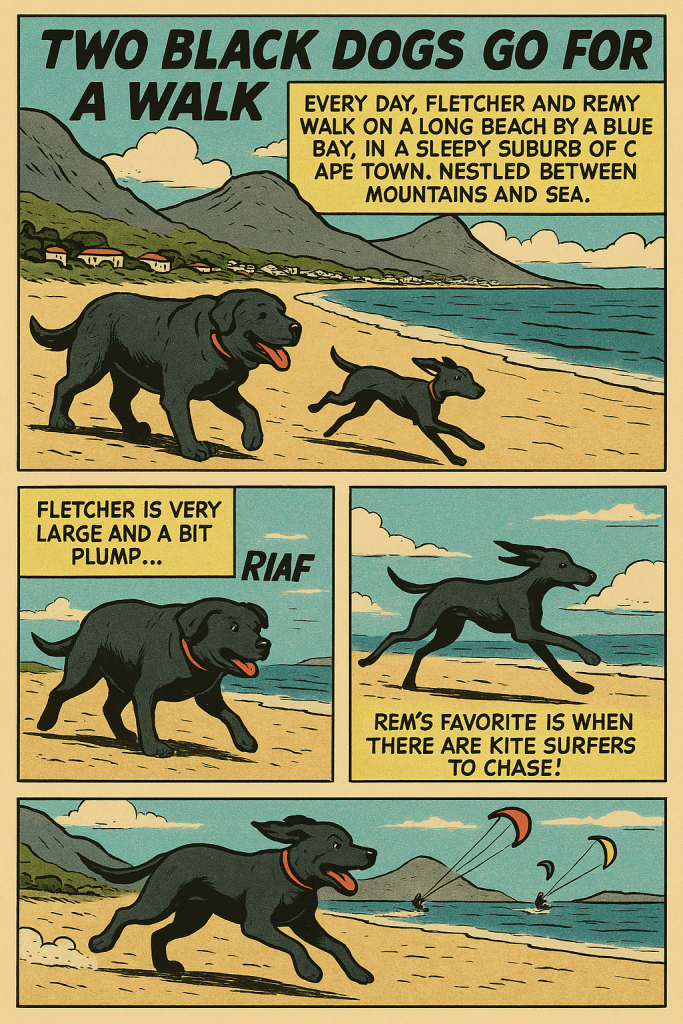

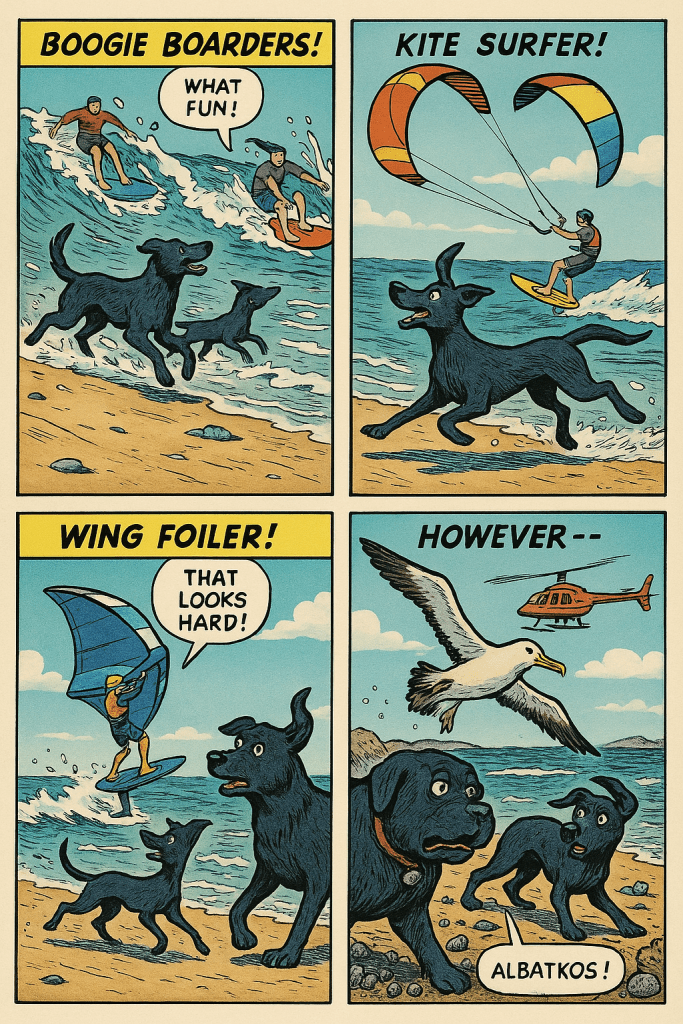

I’ll leave you with a comic book inspired by family pets. This is a fun way to make personalised stories for your kids as and when inspiration strikes. Up to now, art models would render lots of garbled text, (as you can see in the comparison with the Gemini model above), which could be charming at times, but coherent text is just much more fun!

May the ALBATKOS be with you!

Share this article on: